Alan Freed was the first superstar radio DJ, and he more than anyone else was responsible for coining the term “rock and roll.”

Until Freed, “rock and roll” was just a term used in songs of a certain burgeoning flavor. Freed was the first to use the term as an actual defined style of music.

You could say, even though he didn’t invent the music, he invented the genre.

He’s got a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. He’s in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He’s even been called the “real King of Rock n Roll.”

But here’s the thing. Freed is, shall we say, a complicated figure in music history. As a producer he would give himself a writing credit on basically every song, even claiming to have added percussion to a recording by hitting his hand on a telephone book. Several artists sued him over these writing credits. And his participation in payola schemes and tax evasion and such led to his complicated legacy.

He also liked to self-mythologize his history and the events in his life that led to him “inventing” rock-n-roll.

But we know as storytellers that the truth is rarely simple or solitary. Everything is connected.

Check it out. Freed was a relatively popular promoter in Cleveland. He went by the name “Moondog,” which he had taken from a blind, New York street musician/artist. He even sampled the real Moondog’s “Moondog Symphony”—in which the artist played seven instruments (yes, seven)—as the intro to his show, “The Moondog House.”

But Freed’s reach was limited.

Meanwhile, in New York, an investment consortium purchased a struggling radio station, WINS, which had a powerful transmitter and broadcasting rights to Yankees games, but otherwise was in the tank. The investors wanted to build up listenership and flip the station to make a profit. To cut costs, they fired the house band. The American Federation of Musicians (AFM) picketed the station. This was happening during the World Series, so the AFM also picketed Yankee Stadium.

The new owners of WINS were desperate. They needed a draw, so they offered Freed a stupendous contract—$75K/year (in 1954!)—and Freed, with his new market and transmitter, almost overnight became the most popular DJ in the country. Record labels came crawling, begging to get their songs on his show.

The real Moondog also popped up, and sued Freed for using his name. Freed paid, started using his real name, and changed the name of his show to “The Rock and Roll Party.” Not wanting to get into a similar trademark trouble with “rock and roll” as he had with “Moondog,” Freed started a company whose main purpose was to trademark the phrase “rock and roll” for use on his radio show and live concerts. Freed figured he could make money off other DJs, promoters, and labels using “his” phrase.

But “rock and roll” caught on so big so fast, there was no way to claim the royalties. That money-making scheme failed. But Freed ever after took credit.

Do you see? The “invention” of rock’n’roll wasn’t some brilliant moment of divine inspiration. Any number of obstacles—strikes, pickets, lawsuits—accidentally conspired to present Alan Freed with opportunities.

One of my favorite playwrights, Mark St. Germain, told me: “Don’t worry too much about plot. Plot is accidental. Plot is simply what happens when characters go after what they want. The best way to create interesting plot? Throw obstacles at your characters, and see what they do.”

Turning obstacles into opportunities is also the driving theme in this week’s podcast episode with Harrison Bryan. And if that theme isn’t enough to intrigue you, then know this: Harrison is also the most amaaaaazing puppeteer. His puppets also just happen to typically be foul-mouthed. hehehehe

The other takeaway from this story of Alan Freed? Plans are important, but preparation is even better. Because when you’re prepared, you are free to discover and adapt, even if and particularly when your plans don’t go as planned.

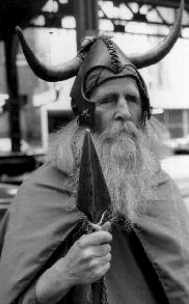

Jason “Where do I get a Viking helmet?” Cannon

Quick plug! I heard that Alan Freed story on one of my favorite podcasts, THE HISTORY OF ROCK MUSIC IN 500 SONGS, which is written, performed, and produced by the brilliant Andrew Hickey. I cannot recommend it highly enough!